I.

Benjamin Labatut’s Bolaño-Sebaldian 2020 novel-like object, Un verdor terrible

(A Terrible Verdure, although Adrian Nathan West’s English translation is

titled When We Cease to Understand the World) has been getting a lot of

attention. It is a fantasy novel where major

twentieth-century scientists and mathematicians are mystics who make their

discoveries through glimpses of the reality behind the veil. Several, but not all, of the figures Labatut

writes about were, in fact, mystics, although the relation, in what I call the

real world, between their work and their mysticism is not so clear.

In fantasy fiction, metaphors are made literal. In A Terrible Verdure, high-cognition scientists

are not just like mystics, but are mystics. What do we get from this particular physics fantasy?

One thing is that the “genius poet” problem is solved. Nabokov somewhere says that the hardest

character to make convincing is the poet of genius, because the author has to

actually be a poet of genius to provide the evidence that the character

is such a thing. Just asserting

genius does not work. The same is true

for physicists and mathematicians. By

using real figures – primarily Fritz Haber, Karl Schwarzchild, Alexander

Grothendieck, Erwin Schrödinger, and Werner Heisenberg – Labatut can use, or at

least name, their actual contributions, while inventing much of the story

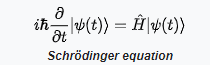

around them. Schrödinger, for example,

comes up with the wave equation at the base of quantum mechanics (non-fiction) while

reenacting sexy scenes from the contemporary novel The Magic Mountain (fiction).

Labatut turns everything mathematical into metaphor, and what else is he supposed to do? “I understand about as much physics as you can without understanding mathematics” he says in an interview in Physics Today. At least the physics problems suggest something in the material world; the chapter on Alexander Grothendieck is especially abstract, since his specialty was pure mathematics, so abstract that even the names of the fields barely mean anything. In my own study of mathematics, I tapped out at real analysis, already getting too abstract for me, so poking around in Grothendieck’s actual work was amusingly pointless.

The speaker here is a Chilean mathematician who, inspired by Grothendieck’s retreat, afraid that math is destroying the world, retired long ago to cultivate his garden:

We know how to use it [quantum mechanics], it works as if by some strange miracle, and yet there is not a human soul, alive or dead, who actually gets it. The mind cannot come to grips with its paradoxes and contradictions. It’s as if the theory had fallen to earth from another planet, and we simply scamper around it like apes, toying and playing with it, but with no true understanding. (187)

Which words are doing all the work? “[A]ctually,” “true”? In another sense, lots of people understand

quantum mechanics, thousands of people. “You

[physicists, but also anyone] need to let the book do what it’s trying to do,

which is going to be harder if you’re a physicist,” Labatut says in the Physics

Today interview, which I think is right, but the other side is that non-physicists

should be clear about what the book is not doing.

II.

In the old days, a novel like this would have likely been

about the dangers of nuclear power and nuclear war, but Labatut barely gestures

in that direction. His recurring

catastrophe is environmental, not the familiar one of climate change, but rather

a disaster of superabundance caused by artificial nitrogen fixing, the great

discovery of chemist Fritz Haber, who was also the father of modern chemical

warfare, an irony that has been explored many times.

Haber is the eventual subject of the first chapter, “Prussian

Blue,” which is a direct imitation of W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn

(1995). The first paragraph covers German

soldiers hopped up on Pervitin, which moves us to post-war suicides, and thus

to cyanide, discovered as a by product of the invention of the chemical pigment

Prussian Blue, which brings us to silkworm cultivation, and so on to Haber and

his life and work. Just like a Saturn

chapter, except shorter and simpler. The

silkworms are taken directly from Sebald, and I mean directly:

The Reich Association of Silkworm Breeders in Berlin, a constituent group within the Reich Federation of German Breeders of Small Animals, which in turn was affiliated to the Reich Agricultural Commission, saw its task as increasing production in every existing workshop, advertising silk cultivation in the press, in the cinema and on radio, establishing model rearing units for educational purposes, organizing advisory bodies at local, district and regional level to support all silk-growers, providing mulberry trees, and planting them by the millions on unutilized land, in residential areas and cemeteries, by roadsides, on railway embankments and along the Reich’s autobahns. (293, Sebald, tr. Michael Hulse)

Labatut compresses the first seventy-three words into two:

The Nazis planted millions of such trees in abandoned fields and residential quarters, in schoolyards and cemeteries, in the grounds of hospitals and sanatoria, and on both sides of the highways that criss-crossed the new Germany. (16, Labatut)

This is the only time I noticed the literal rewriting of a Sebald

sentence (“sanatoria” is added to foreshadow the Schrödinger chapter), but now

I wonder if there are more, and plenty of other bits are dropped in, like the

herring on the last page. I don’t

exactly want to say that Sebald’s sentences and maze of connections are better

than Labatut’s, but they are clearly more complex.

Someone with a copy of Roberto Bolaño’s Nazi Literature in the

Americas (1996) could, I suspect, enjoy a similar, or perhaps quite

different, exercise. See that Physics

Today interview.

I enjoyed When We Cease to Understand the World quite

a lot. But part of that pleasure was recognition, part was flattery, and part

was because it was all kind of easy.

Interesting. I'll have to see what my friends who teach physics and math think about this one.

ReplyDeleteI would love to know. This is from that same interview:

ReplyDelete"I’m trying to be as precise as I can regarding science, but I’m writing for people who have never heard of the word momentum. My readers are ignorant when it comes to physics."

I felt that a lot of the response to the book was giving Labatut the kind of credit you might give someone who'd invented geniuses, rather than found them lying about. Bearing in mind that it was the latter, once I began to get a feel for the kind of vision that had united the disparate narratives, it suddenly began to seem disappointingly banal.

ReplyDeleteThe various elements tick all the right boxes for me. Physics, ideas, Sebald, B. I mean, Sebald already paraphrases and to paraphrase and condense him further as part of a game of association must be worth it. I mean, reflecting about science and physics and the interconnection of things could be worthwhile, too.

ReplyDeleteTicks the boxes - yes! Just the kind of thing I like. Read it if you get the chance.

ReplyDeleteBut as facetious says, well, it all only goes so far. There are other books about these scientists. Labatut includes a number of them in a page of sources. He also includes, on that page, The Rings of Saturn. He is not hiding anything.