Last post for a while, until January, so it had better be a list of books.

Four Best Books of 2015 that are actually more or less from 2015.

1. John Keene’s Counternarratives. I wrote an oblique post mostly about a story telling, from Jim’s point of view, what happened after Huckleberry Finn, which I predict will someday be a famous, much taught story. And it isn’t even the best story in the book. If I had spent the year reading new books, I do not think I would have read a smarter one.

2. Kamel Daoud’s The Meursault Investigation (2013 in French), another counternarrative, The Stranger from the perspective of the brother of the murdered man. Or at least he thinks the Camus novel is about his brother. Maybe he is wrong. The idea of the novel is so obvious I am shocked it had not been done, but the execution of the idea is full of surprises. This one will also be much taught.

3. César Aira’s The Musical Brain (stories originally from 1987-2011 or so), filling a big hole in English. More is more with Aira, and this book has more more than most. “Cecil Taylor” is a masterpiece.

4. Carola Dibbell’s The Only Ones. A post-apocalyptic future with a teenage hero, oh no, but what looks like (and is) a science fiction novel is actually or also a moving study of motherhood about a single welfare mom in Queens. The mother’s voice is worth hearing for its own sake.

Some especially useful second-rate books

1. Ippolito Nievo’s Confessions of an Italian, also new to English this year. The novel mapped out a history of Italian literature I did not know existed, stretching from the 18th century to Italo Calvino. Hugely helpful.

2. Henry James, The Europeans, The American, “The Passionate Pilgrim,” “The Pension Beaurepas,” etc. No one needs to read a previous word of James to read The Portrait of a Lady, but it was instructive to watch him work his way up to it. James was deliberately working his way to a major work, refining and discarding ideas and characters. Really interesting to follow along with him.

3. British poets of the 1890s: William Butler Yeats, Lionel Johnson, Francis Thompson, Robert Bridges, John Davidson, Ernest Dowson (and I could add some who were first-rate: Hardy, Housman, Kipling, and Yeats will graduate in a decade or two). Many of these poets were part of a semi-coherent movement, others just lumped in by temporal coincidence. Reading them in bulk, I began to have doubts about their good taste and good sense, but they made sense together, which is what I was hoping.

The best of the best

Gustave Flaubert, Sentimental Education; A Shropshire Lad, A. E. Housman; Little, Big, John Crowley; Life Is a Dream, Pedro Calderón de la Barca; Germinal, Émile Zola. The confusion of the two dinners at the end of the first act of Richard Bean’s and Carlo Goldoni’s One Man, Two Guvnors; Rosso Malpelo digging for his buried father in Giovanni Verga’s “Rosso Malpelo”; Richard Jefferies falling in love with a trout; Mark Twain getting his watch fixed; John Davidson on the beach with his dogs; Lizzie Eustace trying to memorize Shelley in The Eustace Diamonds; the scene in Marly Youmans’s Thaliad where the little kids in the van drive away from the little boy – no, even better, when they go back for him; and the end of “All at One Point” in Calvino’s Cosmicomics when Mrs. Ph(i)Nk0 creates the universe in an act of generosity – “Boys, the noodles I would make for you!” – which may perhaps be an allegory for what all of these writers were doing for me this year.

Saturday, December 19, 2015

The Wuthering Expectation Best Books of 2015 - the noodles they make for me

Friday, December 18, 2015

One good book, at least, in the literature of the year 1865!

So declares - that is an actual quotation - the greatest critic of his age, Matthew Arnold; the one book is a translation of the letters of the 19th century French Catholic mystic Eugénie de Guérin. See Arnold’s essay “Eugénie de Guérin” in Essays in Criticism, another good book in the literature of the year 1865, so there are at least two.

Ah, Arnold’s nuts; 1865 was a terrific year for literature. 1815 had so few surviving books, or I was so ignorant about them, that I had to think of something to write. In 1865 I can just list books.

First, there’s this:

Charles Dickens completed Our Mutual Friend. Anthony Trollope completed Can You Forgive Her? and can it be true that two more Trollope novels date from 1865, Miss Mackenzie and The Belton Estate? He must have been writing some of them simultaneously, too.

Algernon Swinburne’s debut, the dense, allusive faux Greek play Atalanta in Calydon, made his reputation.

In Russia, Nikolai Leskov’s Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s “Crocodile.”

In Germany, Wilhelm Busch’s Max and Moritz, more or less inventing the comic strip, and the first volume of Adalbert Stifter’s long historical novel Witiko, rumored to be the dullest novel ever written.

In Italy, Giosuè Carducci’s “A Satana,” a toast to progress and rationalism.

In Brazil, José de Alencar’s Iracema, considered the beginning of Brazilian fiction. I’ve read it; it’s second-rate but interesting.

In India, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Durgeshnandini, considered the beginning of Bengali fiction. I have not read it; I’ll bet it’s interesting.

Two novels in French that jump out are From the Earth to the Moon by Jules Verne and Germinie Lacerteux by the Goncourt brothers. I haven’t read either of these, either.

The United States presents some interesting cases. Walt Whitman published Drum-Taps, his Civil War poems, to some success, but they would be eclipsed by the elegies for Abraham Lincoln he published in 1866. Mark Twain published the first version of “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County,” giving Twain his first taste of fame. I find it quite hard to imagine Twain as an unknown writer.

Then there is Hans Brinker; or, the Silver Skates: A Story of Life in Holland by Mary Mapes Dodge, likely the most popular book of the year. I am pretty sure that I have read it, but I would have been no older than ten, so I do not remember a thing about it, beyond the iconically obvious. You cannot say that this book has not survived pretty well. It has more readers than Swinburne or Arnold.

I could keep going (John Ruskin, Henry David Thoreau, Francis Parkman). For me, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Our Mutual Friend make 1865 a landmark year, enriched especially by Leskov’s unique novella. But even within the limits of my ignorance, what a year for literature. “One good book, at least”!

“Nonsense!” said Alice, very loudly and decidedly, and the Queen was silent.

Thursday, December 17, 2015

He reads the Agricultural Reports, and some other books – The Best Books of 1815

We are looking at an 1815 drawing by Hokusai that I copied from p. 194 of Hokusai by Gian Carlo Calza (1999, English translation 2003). Calza suggests that the scene depicts the Azumaya bookshop. The owner is on the right, a delivery boy with a bundle of text on the left, and a customer in the middle, choosing a book.

What book do you think he will buy? Will it be one of the best Japanese books of 1815? What were the best Japanese books of 1815?

I have picked up from what I have read about Japanese literary history that the 19th century is not thought of as a good period, a helpful judgment in that it gives me a good excuse to stay ignorant. I enjoy playing with Best Books posts at the end of each year, but they are mementoes of my ignorance.

How many books from 1815 have I read? I believe three, or perhaps only two, but I did read those books in particular because a long line of readers have kept them alive. If not the best, they are the survivors.

In December 1815, Walter Scott would have topped the Best Books lists with his second novel, Guy Mannering. Well, not Scott, but rather “The Author of Waverley.” I do not know how high The Author of Pride and Prejudice &c. &c. would have ranked with Emma, but she was becoming pretty well-known by this point.

One of these novels is currently among the most popular in the world, while the other has retreated to graduate school, although Scott Bailey read it last spring and made it sound pretty good, if “very plotty.” I’ve read seven Scott novels, but not Guy Mannering; what do I know.

The big celebrity bestseller of the year was Lord Byron’s Hebrew Melodies, a collection of song settings of original lyrics published in an expensive edition. Byron was so popular that he could immediately sell ten thousand copies of even this book. Current selections of Byron, even fat Penguins and Oxfords, come close to ignoring Hebrew Melodies, but it is the home of “She Walks in Beauty.”

It’s the next year, 1816, when miracles start to happen in English poetry.

I know of two great books in German literature from 1815: E. T. A. Hoffmann’s The Devil’s Elixir (or just its first half – I never got this straight), and Part II of the first version of Grimm’s Children’s and Household Tales (Part I is from 1812).

The Hoffmann novel is great fun and a standard classic for German-language readers. No idea why it has never done much in English. Too weird?

The Grimm brothers’ book is of the highest importance. Which book has generated the most additional books, Emma or Grimm’s’ Fairy Tales? This second volume has “Hans My Hedgehog,” “The Goose Girl,” “The Golden Key” with its unending ending. I have read the complete Fairy Tales, but not in this early form. That would be worth doing someday.

So, within the bounds of my ignorance, then: after two hundred years of erosion, three great books left.

The title is borrowed from Emma.

Wednesday, December 16, 2015

Every man, whoever he is, must bow down before the Great Idea - some of the ideas in Devils - Oh, how that book tormented him!

“My friends, all of you, everyone: long live the Great Idea! The eternal, infinite Idea! Every man, whoever he is, must bow down before the Great Idea.” (III, 7.3)

This poor fellow, Stepan Trofimovich, died three days later.

In The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Great Idea is some kind of return to the principles of Russian Orthodox monasticism. I do not think that he is quite there yet in Devils, but the cloud of concepts is forming. This man is dying in the company of a young woman who is an itinerant Bible peddler. He is trapped by his fever in a village of lakeshore fishermen who make their living gouging travelers waiting for the ferry – they have cast down their nets and become fishers of men!

Michael Katz tells me in the introduction that Devils came out of a proto-novel to be titled Atheism. The deathbed conversion of this rationalist character – he is some kind of Turgenev-style Superfluous Man – is one remnant of that idea. Other characters embody different ideologies; I can imagine how some of them were at one point meant to be varieties of atheism, although that notion recedes in the novel Dostoevsky actually wrote.

For example, there are the Chernyshevskians, rationalists who were out to replace the useless reformers of Turgenev’s generation by establishing bookbinding cooperatives and so on.

A book lay open on the table. It was the novel What is to be Done?... Oh, how that book tormented him! (II, 4.2)

Stepan Trofimovich is studying Chernyshevsky in order to defeat his followers’ arguments. His son, a psychotic revolutionary nihilist, offers to “’bring [him] something even better,’” which could mean anything. Could mean, literally, nothing.

The overflow of ideas, of points of view, is, for good readers of Dostoevsky, one of the great strengths of Devils, but presents a real intellectual difficulty. It would take a lot of work to chase them all down, sort, and absorb them. Many later writers and critics happily ignore the competing ideas, pulling out the ones they like. Neither William Faulkner nor the French existentialists had much to do with Dostoevsky’s religious ideas, and they got plenty out of him. László Krasznahorkai engages with Dostoevsky’s religious side. I don’t understand it there, either.

Since it is such a strength of Dostoevsky to allow so many voices and perspectives, even ones he loathes, it was a surprise to see how vicious the famous caricature of Ivan Turgenev is. Sure, he goes after Turgenev’s cosmopolitanism, his ameliorism, sure, sure, but also – this is what shocked me – his prose!

There was always a gorse bush around somewhere (it had to be a gorse or some other plant one needed a botanical dictionary to identify). And there was always some violet tint in the sky, which, of course, no mortal had ever seen before; that is, everyone had seen it, but on one knew how to appreciate it, while “I,” he said, “looked at it and describe it for you fools, as if it were the most ordinary thing.” The tree under which the fascinating couple sat had always to be of some orange hue. (III, 1.3)

Dostoevsky is attacking Turgenev for paying attention to literary art. This is going to be trouble for me, however inventive his man-sized love spiders.

There is a landscape late in Devils, a rarity in Dostoevsky:

The old, black road, rutted by wheels and bordered by willows, extended before him like an endless thread; to the right lay a bare field where the grain had long since been harvested; to the left – bushes and a wood beyond. And in the distance – in the distance lay the scarcely visible line of the railway running off at a slant, with smoke rising from a train; but no sound could be heard. (III, 7.1)

There is not much beauty in Dostoevsky’s Russia. Not much of anything beyond the constant stream of speech, howls, whimpers, and hysterical laughter. “’Oh, what a torrent of other people’s words!’” a character shouts (II, 5.3), in what turns out to be another dig at Chernyshevsky (“You’ve even got as far as the new order? You poor creature! God help you!”). Strictly speaking no more words than in any other novel of the same length, yet that is what I come to the book to see, that torrent of half understood words, all somehow made Dostoevsky’s own.

Tuesday, December 15, 2015

He hated the steak itself - some trouble understanding Dostoevsky's Devils - we'd gaze at him for the rest of our lives and be afraid of him

Writing about Emma, I idly wondered if I should ever write about books I have only read once. Now I will reinforce the idea by writing about a book I have read once and do not understand.

Of course he was “strange,” but there was much that was unclear about all of this. There was some hidden meaning to it. (Part I, Ch. 4.3)

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Devils (1872, tr. Michael Katz) was baffling. It is the most chaotic Dostoevsky I have ever read, far more so than The Brothers Karamazov (1880), which I had thought was the outer limit for a functioning novel. Maybe I was right.

“It always seemed that you’d take me off to some place where an enormous, man-sized evil spider lived and we’d gaze at him for the rest of our lives and be afraid of him. That’s how we’d spend our mutual love.” (II, 3.1)

Now, I love those lines. I recently read a Dadaist novel, actually about Dadaists and their associates and ideas, A Brief History of Portable Literature by Enrique Vila-Matas (1985), a deliberately crazy, random book, but I do not think Vila-Matas got anywhere close to what this (crazy) woman says to her (crazy) lover as they argue about whether they should run away to Switzerland, split up, commit suicide, etc.

The Argumentative Old Git wrote a thorough catalog of the novel’s obstacles to understanding. The inconsistent narrator, the seemingly random introduction of characters and the way major characters vanish for long stretches and minor characters suddenly take over the book “as Dostoyevsky’s attention is captured by other matters,” the unsettling shifts in tone as a comic novel lurches into terror, and range of semi-coherent and incompatible ideas.

“His sister? His sick sister? With a whip?” Stepan Trofimovich cried out, as if he himself had suddenly been thrashed with a whip. “What sister? Which Lebyadkin?” (I, 3.5)

That is just what I had been asking at that exact moment. How rare to be in such sympathy with a Dostoevsky character.

Some of these problems are artistic flaws, problems Dostoevsky would have fixed if he were the kind of writer who went back and fixed problems. The abundance of ideas and points of view is not a flaw but a difficulty. The weird narrator, too, or so I guess after one reading.

The best part of the novel, which jolts into movement after about four hundred pages and really only occupies about 150 pages near the end, is about a small group of revolutionary anarchists who murder one of their associates. A whole series of violent deaths precede and follow. Critics frequently refer to Devils, but I do not remember ever seeing a reference that was not to this one part of the novel. I understand: it is bloody and tense and although nightmarish it is coherent, and is thus memorable.

He counted every piece of steak Peter put into his mouth; he hated him for the way he opened his mouth, chewed his food, and smacked his lips over the fattiest morsels; he hated the steak itself. (III, 4.2)

Randomness, or what looks like randomness, is very hard to remember. The first four hundred and large chunks of the last three hundred pages of this novel are going to be darn hard to remember.

Sunday, December 13, 2015

After a little more discourse in praise of gruel… - Emma's food, Emma's jokes

From Chapter 12, part of the hypochondria theme, where Emma’s father tries to bully everyone into eating gruel before bed.

“You and I will have a nice basin of gruel together. My dear Emma, suppose we all have a little gruel.”

Emma could not suppose any such thing…

There is a surprising amount of gruel in Emma, but also more appetizing food, almost all of it attached to her father and his attempts to deny the pleasure of others.

“An egg boiled very soft is not unwholesome. Serle understands boiling an egg better than any body. I would not recommend an egg boiled by any body else – but you need not be afraid – they are very small, you see – one of our small eggs will not hurt you.” (Ch. 3)

Ah, this is the passage where Mr. Woodhouse says “’I do not advise the custard’” – this is the custard served at his own house, at his own table.

Later discussions involve pork loins eaten with “’a boiled turnip, and a little carrot or parsnip,’” and sweetbreads with asparagus. Emma has the latter prepared for a guest who particularly savors it, even though she fears her father will ruin the pleasure in it (which he does).

Almost every previous fiction writer, and all too many subsequent ones, would not bother to specify the dish. “Emma had a special dish prepared for her” or something like that would be sufficient. Similarly with the level of detail about the gruel or pork or baked apples. Why include anything so ordinary and boring? Or the scene where Emma and Harriet are fabric shopping, how can that be interesting?

Samuel Richardson, Austen’s favorite novelist, would never have included any of this. In his hands, it would have been so tedious. In hers, the passages are full of jokes and insights into characters. It was Austen who taught me to pay attention to the kind of transportation under discussion, that chaise and barouche-landau are not just types of carriages but contain a lot of meaning, particularly about class and status.

Walter Scott was at the same time working through some of the same issues. He realized that the materiality of his fictional world made up a good deal of the difference between the past and the present, and between Scotland and England, so he began packing more stuff into his books. Austen was doing something trickier. What reader, even the Prince of Wales, needed to read about boiled eggs?

I do not want to argue that Austen and Scott represent progress, exactly. They had all read Robinson Crusoe (1719). Talk about a material novel.

Maybe next time I read Emma I will collect more of her jokes. Everyday comedy, aphorisms (“Human nature is so well disposed towards those who are in interesting situations, that a young person, who either marries or dies, is sure of being kindly spoken of,” Ch. 22), jokes of character:

Mr. Knightley seemed to be trying not to smile; and succeeded without difficulty, upon Mrs. Elton’s beginning to talk to him. (Ch. 36)

I know it is not everyone’s Austen, but mine is the one with a sting.

Thanks to Dolce Bellezza for getting a readalong moving.

Friday, December 11, 2015

Emma's resources - she was not unwilling to have others deceived

How does Austen restore goodwill towards her heroine after mocking her for snobbery, callowness, and junky reading? And her painting, I forgot about Emma’s portraits.

She was not much deceived as to her own skill either as an artist or a musician, but she was not unwilling to have others deceived… (Ch. 6)

That’s Austen rubbing it in, although Emma delivers her own kind of self-mockery when, examining one of her portraits she declares, honestly enough, “’ The corner of the sofa is very good.’” Not the highest priority in a portrait.

I mean, Dolce Bellezza was afraid she “would throw the book down in disgust at [Emma’s] interfering, meddlesome ways.” Austen has some work to do.

Emma acquires some self-knowledge as the novel moves along, which is a big help. A better musician moves to town, good enough the sentiment in the above quotation is no longer true. And then Mrs. Elton moves to town – so many characters suddenly move to this little town – and provides a contrast so severe that the acquisition of self-knowledge is greatly furthered.

Meaning, it would be too embarrassing to sound like Mrs. Elton. In Chapter 10, it is Emma who brags about her “active, busy mind, with a great many independent resources” (music, reading, and so on). Later, it is the vain, aggressive, vulgar newlywed who cannot stop talking about her “resources”:

“Blessed with so many resources within myself, the world was not necessary to me. I could do very well without it. To those who had no resources it was a different thing; but my resources made me quite independent.” (Ch. 32)

At the same time she practically boasts of not practicing the piano, of not doing anything except visiting. “’Insufferable woman!’ was [Emma’s] immediate exclamation” – immediately once in private, that is. Meeting a living self-parody can be a great aid to reform.

The problem of “resources” is real, especially for the women in Emma. Not just women – Emma’s father made insufficient “mental provision” for “the evening of life,” and as a result he is an enormous pain for everyone else. It is the women, though, especially those of a higher class, who have great trouble simply finding enough to do within the narrow constraints they are allowed. The mental provision – skill at the piano or the discipline to read a difficult book – is to allow them to sit alone in a quiet room, as Pascal wrote.

Otherwise, much of the remaining activity is gossip. In Giovanni Verga’s Sicilian novels of small town life, The House by the Medlar Tree and Mastro Don-Gesualdo, the main entertainment, the true entertainment for most people, is gossip, the more poisonous the better. The town in Emma is a friendlier, healthier place than Verga’s Sicily (understatement), more truly social, but much of the story is about the dangers of too much gossip.

Thank goodness for the invention of television, which allowed people at all levels to direct their gossip at imaginary people.

Thursday, December 10, 2015

And very good lists they were - Emma should read better books

The other clever structural device I noticed in Emma, aside from the inset detective novel, is that it made real use of the three-volume novel format forced on Jane Austen by her publisher. The first volume is practically a standalone novella.

Smart, restless, bored Emma Woodhouse, having successfully played matchmaker for her best friend, decides to give it another go with a cute, dim-witted protégée, Harriet Smith. Along the way she misinterprets every possible romantic signal from every possible direction, makes a (mild, comic) mess of things, and learns a (mild, comic) lesson about hubris. Several key characters are mentioned but kept offstage; they will be brought on in Volume 2 as part of a more complex version of the story rehearsed in the first volume. The first volume would have been a minor comic classic on its own.

Early on, Emma’s older friends spend the most tedious chapter in the novel (Ch. 5) criticizing her – what? her lack of wisdom and discipline – her youth, I am tempted to say. This chapter more than any other reminds me that Austen is an 18th as well as a 19th century novelist.

Is this Emma or Émile? Is Harriet suitable as a friend of Emma? She “’is not the superior young woman which Emma’s friend ought to be’” – meaning, Emma is bright and Harriet is dim. But “’[t]hey will read together’” – “’it will be an inducement for [Emma] to read more herself.’” Emma’s friends are saying she does not read enough.

“Emma has been meaning to read more ever since she was twelve years old. I have seen a great many lists of her drawing up at various times of books that she meant to read regularly – and very good lists they were – very well chosen, and very neatly arranged – sometimes alphabetically, and sometimes by some other rule. The list she drew up when only fourteen – I remember thinking it did her judgment so much credit, that I preserved it some time…”

Many book bloggers, including this one, will read this passage with some wincing and grimacing. The lists would be of improving books – this is the 18th century idea. In the previous chapter, Harriet and Emma dismiss Harriet’s farmer suitor because he does not read – well, he reads, “the Agricultural Reports and some other books,” and also The Vicar of Wakefield, a novel but one that would count as a wholesome, improving book, as 18th century novels go – but he does not read Gothic novels, in fact “’[h]e had never heard of such books before I mentioned them.’”

Here we have Austen attacking her own characters for their backwards snobbery, their dismissal of a man for not reading popular trash. She does not even give them the excuse that he doesn’t read novels. Austen can be so mean. Several chapters later, Austen adds to the insult:

[Emma’s] views of improving her little friend’s mind, by a great deal of useful reading and conversation, had never yet led to more than a few first chapters, and the intention of going on to-morrow. It was much easier to chat than study… the only literary pursuit which engaged Harriet at present, the only mental provision she was making for the evening of life, was the collecting and transcribing all the riddles of every sort that she could meet with… (Ch. 9)

The phrase in bold is the author openly mocking her characters. The heck with free “indirect” style!

Note that the riddles are an early thematic reference to the idea of the detective novel which will be developed in the next volume. Emma is a well-controlled novel.

Wednesday, December 9, 2015

She only gave herself a saucy conscious smile about it, and found amusement in detecting - Emma as undetectable detective fiction

Emma, the anonymous novel by “The Author of Pride and Prejudice &c. &c.,” published two hundred years ago this month, the great “novel of deceit and detection” as P. D. James calls it. Many people are doing a bicentennial reading. Me, too.

When I first (also last) read the novel, I did not know that it was detective fiction. The mystery novel structure was undetectable. This time, knowing the story, it was so blatant I might have called some of the devices clumsy if I did not know that it was, really, fundamentally, invisible. The magician had taken me backstage to show me some of her tricks. The demonstration of those may well be themselves tricks, the existence of which will be revealed the next time I read Emma.

I sometimes wonder if I should ever write about books I have only read once. The errors I must make.

A young woman moves to a small town to live with her aunt and grandmother. The detective in the title tries to figure out why – was she, for example, romantically involved with her best friend’s husband? The substance of the mystery is not that exciting, but for structural purposes it hardly matters. There are clues, red herrings, mysteries within mysteries, mysteries alongside mysteries, revelations, all of that stuff, all before there was any such thing as a detective novel.

Then there is the comedy, more to the point. Inspector Emma turns out to be a terrible detective, a great comic blunderer, Clouseau with an English accent. And this is part of the ethical meaning of the novel, which is itself a good trick.

For example, in Chapter 34, secondary characters spend two pages arguing about who will pick up the mail, a scene just as dull as it sounds:

“The post-office is a wonderful establishment!" said she. – “The regularity and despatch of it! If one thinks of all that it has to do, and all that it does so well, it is really astonishing!”

“It is certainly very well regulated.”

[blah blah blah]

The varieties of hand-writing were farther talked of, and the usual observations made.

I wonder what I was thinking a decade ago when I read that sentence. Probably something like “man, what a dud sentence; The Author of Pride and Prejudice &c. &c. is kind of overrated.” This time, though, it was amusingly obvious that the entire scene was full of clues to the mystery, and that, even better, Detective Emma realizes that it is full of clues – “She could have made an inquiry or two, as to the expedition and the expense of the Irish mails; – it was at her tongue’s end – but she abstained” – but as a bad detective she misinterprets them, and as a worse detective and obedient reader, I followed right along after her. She is the smartest character in the novel, so of course I trusted her.

The first time, it was entertaining to try to solve the mystery along with the detective; the second, it was even more enjoyable to see how The Author of &c. &c. had so skillfully led me along by the nose.

The title quotation is from Chapter 51, remorselessly torn from its context.

Tuesday, December 8, 2015

Silly, rotten, derivative, but sane - George Bernard Shaw's The Sanity of Art

George Bernard Shaw’s little books or pamphlets on Henrik Ibsen and Richard Wagner – The Quintessence of Ibsenism (1891) and The Perfect Wagnerite (1898) – were so much fun that I rounded out the trilogy with The Sanity of Art (1895). The three essays have been collected under the boooring title Major Critical Essays, but I read online scans of old versions.

The Sanity of Art is a demolition job against Max Nordau’s screed Degeneration (1892) which was having a vogue in England. Nordau’s book is a classic in the “everything is going to hell” genre, especially interesting because 1) the sad, terrible irony of what the Nazis would do with this idea (Nordau was a founder of Zionism), and 2) he goes after all of the wrong targets. It is amazing. Ibsen, Wagner, Tolstoy, Wilde, the pre-Raphaelites, Impressionist painting, and this art is not merely bad or harmful but insane, which is hardly their fault as they are only symptoms of the overall degeneration of the human brain.

Alternatively, Nordau hits all of the right targets, since everything only gets worse, across the board. I mean, if you think Whistler, Monet, and D. G. Rossetti are evidence of the end of civilization, wait’ll you see what Picasso, Kandinsky, and Duchamp are going to do.

Shaw argues that the relevant works are “wholly beneficial and progressive, and in no sense insane or decadent” (29), which is perhaps too easy of an argument, too much of a bug-squashing. He calls it “riveting his book to the counter” with “a nail long enough to go through a few pages by other people as well” (113).

More interesting is watching Shaw work through the central problem of contemporary arts criticism, telling the rotten imitators from the real artists.

Thus you have here again a movement which is thoroughly beneficial and progressive presenting a hideous appearance of moral corruption and decay, not only to our old-fashioned religious folk, but to our comparatively modern scientific Rationalists as well. And here again, because the press and the gossips have found out that this apparent corruption and decay is considered the right thing in some influential quarters, and must be spoken of with respect, and patronized and published and sold and read, we have a certain number of pitiful imitators taking advantage of their tolerance to bring out really silly and rotten stuff, which the reviewers are afraid to expose, lest it, too, should turn out to be the correct thing. (69)

I’m not sure if Shaw is being too hard on the reviewers or too easy. But he is correct that the art of our time almost always looks decadent. No critic is wrong when he complains that there is too much derivative trivia out there, and too much garbage.

Even at such stupidly conservative concerts as those of the London Philharmonic Society I have seen ultra-modern composers, supposed to be representatives of the Wagnerian movement, conducting pretentious rubbish… And then, of course, there are the young imitators, who are corrupted by the desire to make their harmonies sound like those of the masters whose purposes and principles of work they are too young to understand, and who fall between the old forms and the new into simple incoherence. (42-3)

In the identical riff in the section on Impressionists, Shaw says that Whistler’s imitators paint “figures placed apparently in coal cellars,” making them look, if I do not understand what they are doing, insane. If I do understand, they merely look mediocre and derivative.

The Sanity of Art is bracing for a critic, and is only incidentally itself a rant. Do your jobs, critics! Yessir, Mr. Shaw.

Page numbers from the 1907 edition I found at Hathi Trust.

Sunday, December 6, 2015

Georg Trakl's Poems - the degrees of madness in black rooms

A German Literature Month post at roughghosts reminded me that I had wanted to revisit the poems of Georg Trakl. James Reidel has been translating Trakl’s books as books, meaning that the recent Poems (2015, Seagull) is a version of Poems (1913), Trakl’s only book during his short life. A translation of Trakl’s posthumous poems will be published next year.

The Robert Firmage translation, Songs of the Departed (2012, Copper Canyon) included more poems, more variety of poems, a long essay on Trakl, and best of all the German texts. Firmage selects and mixes up the poems, for understandable reasons, which makes it a pleasure to be able to squint hard and read Trakl in an approximation of the way his contemporaries read him.

One of those pleasures, paradoxically, is to watch Trakl at work. He repeats himself more than I had known. Black, yellow, brown, blue; angels, silence, shadows; the autumn woods and empty fields; the same elements arranged and rearranged until they do whatever it is Trakl thinks they should. Sometimes, in English, they do not look like much more than the usual Trakl-stuff. Other times, even in English, they show why a poet with one short book is still read:

from Outskirts in the Föhn

The place lies dead and brown with evening,

The air permeated with a ghastly stench…

Sometimes a howl rises out of some vague urge,

In a crowd of children a frock flies red

A rat choir squeaks love-struck in the garbage,

Women carry bushel baskets of offal…

A canal suddenly spews congealed blood

From the slaughterhouse in the still river.

The föhn gives the few sparse wildflowers more colour

And slowly the redness creeps through the flood.

And then the poet spends the last two stanzas looking at the clouds!

One sees too a ship foundered upon the cliffs

And every now and then rose-coloured mosques.

Another of Trakl’s favorite words in Poems is “föhn,” the warm Mediterranean wind that blows across the alps and drives Austrians mad. I think of Trakl as a visionary poet – anyone who includes so many angels in his poems risks the label – but this poem is nothing if not specific, just what a boy sees on a walk at the edge of Salzburg, you know, near the slaughterhouse, enjoying the sky and wind even if it gives him a bit of a headache.

Poems has several short sequences of poems, all of which Firmage omits, all of which seem vaguely related to each other, full of pregnant farm girls and death, full of great, horrifying lines:

One bright green fluorishes, another rots

And toads are sleeping throughout the young leeks. (“Bright Spring,” 1)

Föhn-blown leafless limbs beat the windowpanes,

A wild labour swells a farmwife’s belly.

Black snow is trickling down into her arms;

Golden-eyed owls flutter about her head…

Red evening wind rattles through the windows;

Out of this a black angel emerges. (“In the Village,” 3)

Whatever I lose in rhythm and rhyme – I have looked at the German; a lot – I can say that Reidel gives a strong sense of Trakl.

The degrees of madness in black rooms,

The shadows of the old ones under open doors,

There Helian’s soul reveals itself in the pink mirror

And snow and leprosy drop from his forehead. (from “Helian”)

Friday, December 4, 2015

A shrill music, a laughter at all things - Dionysian Walter Pater

Max Beerbohm’s “Hilary Maltby and Stephen Braxton” includes a joke that requires some readerly inference:

… when Braxton’s first book appeared fauns had still an air of novelty about them. We had not yet tired of them and their hoofs and their slanting eyes and their way of coming suddenly out of woods to wean quiet English villages from respectability. We did tire later.

There must have been so, so many of those things. Walter Pater wrote one of them, his Imaginary Portrait “Denys l’Auxerrois,” and provided the intellectual support for some of the others in several of the essays in Greek Studies (1894). Dionysus was one of Pater’s subjects. This mild, ascetic man and his theoretical bacchanals.

Denys is the god Dionysus in a degenerate medieval form. He mysteriously appears in Auxerre as a child, becomes an organ-builder and musician, and leads the townspeople into frenzy.

The hot nights were noisy with swarming troops of disheveled women and youths with red-stained limbs and faces, carrying their lighted torches over the vine-clad hills, or rushing down the streets, to the horror of timid watchers, towards the cool spaces by the river. A shrill music, a laughter at all things, was everywhere.

The vintage becomes, of course, especially good. Wine snobs may sneer: sure, the vintage of Chablis! Now, now.

But Pater is up on the latest scholarship, as he shows in Greek Studies, and his Dionysus is not the triumphant god of the Bacchae of Euripides but rather a true fertility god, flourishing but also dying with the seasons, so that it is not the unbelievers but Denys himself who is torn apart in a frenzy.

The monk Hermes sought in vain next day for any remains of the body of his friend. Only, at nightfall, the heart of Denys was brought to him by a stranger, still entire. It must long since have mouldered into dust, under the stone, marked with a cross, where he buried it in a dark corner of the cathedral aisle.

Denys’s life and death are also pictured in a stained glass window that gets “Pater’s” attention, putting a frame around the story. I have been in that very cathedral, I believe I have even heard the organ there, but no one pointed out the window or where the heart of a reincarnated Greek god was kept as a relic.

I might not have read Pater’s Greek Studies if I had not just read The Birth of Tragedy (1872). Pater is less fanciful, or bold, than Friedrich Nietzsche. In particular, he does not think Euripides destroyed tragedy but rather takes The Bacchae as a useful and genuine example of Greek religious expression. He turns the Euripides play into another imaginary portrait, some mix of criticism, like a summary with commentary, and fiction, but with essayistic digressions. He does the same for the myths of Demeter and Persephone and the Hippolytus of Euripides. As criticism, it is odd, but enjoyable, personable.

The Renaissance is easily Pater’s best book, followed by the 1888 collection Appreciations, which I have barely mentioned, but further reading in Pater was rewarding, if often confusing. Imaginary Portraits deserves a fresh look, but by whom, exactly?

Thursday, December 3, 2015

he loved the distant - Pater's Imaginary Portraits - Anything so beautiful is not to be seen now

These semi-fictions Walter Pater wrote, like “The Child in the House” or the four in Imaginary Portraits (1887), they should lead to a Pater revival. They are not so different than some of the imaginary portraits in W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn (1995) or László Krasznahorkai’s Seiobo There Below (2008), where aesthetic ideas are often the subject of the fiction. In Pater’s stories, as in Seiobo, beauty is apparently trying to murder its devotees.

People are into hybrid works now, right? Pater was an early Hybridist.

Two of the Imaginary Portraits are about artists. “Sebastian von Storck” is about a Dutch painter who dies young from excessive objectivity and exposure to Spinoza, while “A Prince of Court Painters” is Jean-Antoine Watteau, another painter who dies young, a real painter, I will note. The narrator ends her account of Watteau’s life with:

He has been a sick man all his life. He was always a seeker after something in the world that is there in no satisfying measure, or not at all.

Pater was, or thought he was, related to Watteau, and the story is narrated by a Pater. Little autobiographical details show up in surprising place in the Portraits. “Sebastian von Storck” has autobiographical touches, too, often I think inverted:

For though Sebastian von Storck refused to travel, he loved the distant – enjoyed the sense of things seen from a distance, as on wide wings of space itself, far out of one’s actual surroundings.

His ideal is “an intellectual disinterestedness, of a domain of unimpassioned mind,” which hardly sounds like the champion of subjective criticism, yet what are the Imaginary Portraits if not things seen from a great distance?

“Denys l’Auxerrois” is about a werewolf, sort of. You would think that would make it more exciting than it is. The story is set in early modern Auxerre, which Pater calls “the prettiest town in France,” an opinion I find plausible. It is also the center of the production of Chablis, which is why Pater uses it, the combination of beauty and wine. But I want to save this one.

Finally – Imaginary Portraits is a short book – “Duke Carl of Rosenmold” begins as if it is a German novella, with a pair of skeletons, male and female, discovered when a giant tree comes down in a storm. Could it be the mysteriously vanished Duke? (Sure, why not). But then the bulk of the story, the flashback, is about the Duke’s failed half-measures to improve and civilize his duchy with “French plays, French architecture, French looking-glasses,” to be the “Apollo of the North.” German literature fails him – “Was German literature always to remain no more than a kind of penal apparatus for the teasing if the brain?” – while German music does better. He travels, pursuing the ideals of Greece and Italy, but somehow never sets foot outside of Germany.

The story is a parody of the life of Goethe. First, assume Goethe is himself the Duke of Weimar, or the Duke of Weimar is somehow Goethe, and that he is born too soon, active at the beginning of the 18th century rather than the end, when the aesthetic and intellectual ground for his ideas have not been prepared, Goethe without Lessing and Herder. This is all stated plainly on the book’s last page. The story actually ends with the image of young Goethe skating. He was a perfect ice skater, He did everything well.

“There skated my son, like an arrow among the groups. Away he went over the ice like a son of the gods. Anything so beautiful is not to be seen now. I clapped my hands for joy. Never shall I forget him as he darted out from one arch of the bridge, and in again under the other, the wind carrying the train behind him as he flew.”

Wednesday, December 2, 2015

absolutely the reddest of all things - Pater's imaginary self-portrait - this pressure upon him of the sensible world

Walter Pater developed a strange, oblique form of fiction he called the “imaginary portrait.” Writing about Marius the Epicurean (1885), Pater’s only attempt at a novel-length “portrait,” I wrote that he had no gift for character or story. His “portraits” are fictions merged with essays, so their pleasures are closer to those of criticism. In fact, much of his criticism – a startling amount, I thought – consists of imaginary portraits created from life, or literature, Leonardo da Vinci or the Hippolytus of Euripides turned into the subjects of not short stories, exactly, and not biographies, but “portraits.” Whatever those are.

I am honestly not sure that I quite know how to read them yet.

“The Child in the House” (1878) is Pater’s most plainly autobiographical example. The narrator describes a man remembering, in various ways, his early childhood in a particular house, and how a range of sensory experiences formed his aesthetic and ethical sense.

Sensibility – the desire of physical beauty – a strange biblical awe, which made any reference to the unseen act on him like solemn music – these qualities the child took away with him, when, at about the age of twelve years, he left the old house, and was taken to live in another place.

Anyone who ever wonders what Pater means, or what I mean, by the link between ethics and aesthetics, “The Child in the House” is not a bad place to go. Sometimes the idea is as simple as the character learning about kindness or dignified death from this pets – “the white angora, with a dark tail like an ermine's, and a face like a flower, who fell into a lingering sickness, and became quite delicately human in its valetudinarianism, and came to have a hundred different expressions of voice” – and sometimes something more complex, like the discovery of the sublime, when “this desire of physical beauty mingled itself early the fear of death – the fear of death intensified by the desire of beauty.”

Much of the child’s aesthetic development is attached to specific sensory impressions, as he is “played upon by them like a musical instrument.” The light on the snow, an illustration of Jacob wrestling the angel, an encounter with the open grave of a child, “this pressure upon him of the sensible world.”

If this sounds like something out of Proust, yes; “The Child in the House” is the most Proustian bit of pre-Proustian prose I have ever seen, most blatant in the child’s encounter with a “a great red hawthorn in full flower,” a clear reference to Marcel’s tearful embrace of his beloved hawthorn in Swann’s Way (1913), the most pathetic scene in literature.

… the beauty of the thing struck home to him feverishly; and in dreams all night he loitered along a magic roadway of crimson flowers, which seemed to open ruddily in thick, fresh masses about his feet, and fill softly all the little hollows in the banks on either side. Always afterwards, summer by summer, as the flowers came on, the blossom of the red hawthorn still seemed to him absolutely the reddest of all things; and the goodly crimson, still alive in the works of old Venetian masters or old Flemish tapestries, called out always from afar the recollection of the flame in those perishing little petals, as it pulsed gradually out of them, kept long in the drawers of an old cabinet.

It is as if Pater is tracing his career, his affinity for Renaissance art, to the color of childhood hawthorn petals.

Tuesday, December 1, 2015

Pater analyzes and reduces - What effect does it really produce on me?

Rummaging through the poets of the 1890s, and reading the letters of Oscar Wilde, I had one constant thought: “I need to read more Walter Pater.” These Decadents and their Walter Pater.

Now I have read more Pater, four books on top of The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry (1873), and I am baffled. What seems to have happened is that Pater’s disciples pulled a handful of passages – more like lines – out of The Renaissance and built an aesthetic out of them.

To burn always with this hard, gem-like flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life… For art comes to you proposing frankly to give nothing but the highest quality to your moments as they pass, and simply for those moments’ sake. (“Conclusion”)

And similar Greatest Hits of the Art For Art’s Sake aesthetic, not exactly out of context, but getting there. For Pater himself was by temperament nothing like a decadent, a scholar more than an aesthete, an Epicurean of the ascetic kind. He is devoted to nothing but beauty and pleasure, and what is more pleasurable than analyzing poetry?

What is this song or picture, this engaging personality presented in life or in a book, to me? What effect does it really produce on me? Does it give me pleasure? and if so, what sort or degree of pleasure? (“Preface”)

We are almost all Paterian critics now – in my case, much more so than I had realized – but many of his descendants, knowing and otherwise stop here. But Pater keeps going:

The aesthetic critic, then, regards all the objects with which he has to do, all works of art, and the fairer forms of nature and human life, as powers or forces producing pleasurable sensations, each of a more or less peculiar or unique kind. The influence he feels, and wishes to explain, by analysing and reducing it to its elements… His end is reached when he has disengaged that virtue, and noted it, as a chemist notes some natural element, for himself and others… (“Preface”)

So Pater is one of those critics who wants to be “scientific” somehow? No, not remotely. He is a sincere devotee of pleasure and beauty. The chemistry business is just a metaphor.

Some of Pater’s rhetoric makes more sense set against Matthew Arnold’s guff about “objective” criticism, all of his bluster about “high seriousness” and understanding the “truth” of the artistic object. Any given piece of criticism by Arnold has plenty of insights, but I find his rhetoric hard to take. Pater, the “subjective” critic, is just as interested in the truth of the work of art, but is open about the process of aesthetic experience, the steps it takes to reach that truth. Pleasure in one aspect of art pulls him, and me, in to others. An exciting plot leads me to an interesting character who tricks me into thinking about an ethical question which directs me to the author’s rhetoric.

Arnold does this, too, everyone does. Pater’s transparency does make clearer the possibility of other ways into a work of art, responses from other directions. But everyone, in the end, is studying the object. In practice, Pater’s criticism looks a lot like Arnold’s. The “me” is hardly visible.

Or it is channeled elsewhere. Pater uses a strange, original form for that purpose. I will write something about it, something even more shallow and uncomprehending than this post.

The Renaissance is a great book, by the way, a great book about Renaissance art. Just ignore everything I wrote here. The Leonardo chapter, the Winckelmann chapter – so rich in ideas.

Wednesday, November 25, 2015

the delight felt at the annihilation of the individual - The Birth of Tragedy, in which Nietzsche aspires to the condition of music

My final German Literature Month book (look at all of the participants!) will be The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music (1872) by Friedrich Nietzsche, his first book, an imaginative consideration of the psychological impulses that led to the creation, degeneration, and recovery – in the works of Richard Wagner – of Greek tragedy. It is a strange book, not scholarly yet based on the latest German classical archaeology and anthropology, leaping far beyond the actual evidence, difficult, exhilarating, and preposterous.

Greek tragedy is, for Nietzsche, in the first form visible to us, the plays of Aeschylus, a balance between the rational and the irrational, the steady Apollonian and frenzied Dionysian sides of the human personality. The chorus, the music, is the Dionysian side.

It is vain to try to deduce the tragic spirit from the commonly accepted categories of art: illusion and beauty. Music alone allows us to understand the delight felt at the annihilation of the individual. (Ch. 16, p. 101)

A strongly Schopenhauer-like claim, and one with which I roughly agree. Literature, even at its craziest, is typically way over on the Apollonian side compared to dance and music. Poetry moves towards the Dionysian to the extent that it resembles music. I am beginning to sound like Walter Pater, or Pater sounds like Nietzsche.

Tragedy goes into sharp decline in the hands of the innovative parodistic screwball Euripides, mostly because he pulls too much music out of the chorus, destroying the Dionysian side of tragedy. But Nietzsche forgives Euripides, for he is just a pawn of the true villain:

For in a certain sense Euripides was but a mask, while the divinity which spoke through him was neither Dionysos nor Apollo but a brand-new daemon called Socrates. Thenceforward the real antagonism was to be between the Dionysiac spirit and the Socratic, and tragedy was to perish in the conflict... The marvelous temple lies in ruins; of what avail is the destroyer’s lament that it was the most beautiful of all temples? And though, by way of punishment, Euripides has been turned into a dragon by all later critics, who can really regard this as adequate compensation? (Ch. 12, 77)

Turned into a dragon! Like the greedy, murderous giant Fafner in Das Rheingold and Siegfried.

The creation of opera by, let’s say, Monteverdi in the 17th century should restore the balance, but Nietzsche does not believe such a thing happened before Wagner. To use Shaw’s phrase, Rossini and Verdi are “opera, and nothing but opera,” not tragedy. I did not understand Nietzsche’s argument, and would be pleased to dismiss it as prejudice, but I am too ignorant to do so.

Our art is a clear example of this universal misery: in vain do we imitate all the great creative periods and masters; in vain do we surround modern man with all of world literature and expect him to name its periods and styles as Adam did the beasts. He remains eternally hungry, the critic without strength or joy, the Alexandrian man who is at bottom a librarian and scholiast, blinding himself miserably over dusty books and typographical errors. (Ch. 18, 112)

Non-Wagnerian opera “is the product of the man of theory, the critical layman, not the artist. (Ch. 19, 115), not even Socratic but, per the previous passage, Alexandrian, desiccated, the province of scholiasts. I know, this is as bizarre and wrong-headed a description of Rossini as I can imagine.

Luckily Bach and Beethoven, alongside Kant and Schopenhauer, created the superstructure – “succeeded in destroying the complacent acquiescence of intellectual Socratism” – that allowed Wagner to save the day, at least for a while.

The end of The Birth of Tragedy is extraordinary. Nietzsche is arguing for the value of the Dionysian impulse, arguing that you Swiss and Prussian and Victorian squares seek out the Dionysian a little more.

The reader may intuit these effects if he has ever, though only in a dream, been carried back to the ancient Hellenic way of life. (146)

What a line – “if”! In a dream, perhaps, but also, possibly, in some other way, such as time travel, or, and this is an example from German literature, madness, like that of poor Friedrich Hölderlin who at times seemed to believe he lived in Classical Greece. I wonder if the line is actually referring to Hölderlin. I wonder if poor Nietzsche ever thought it might refer to himself.

After a pause for the holiday, I will return to the idea of the Dionysian with the help of Walter Pater.

Page references are to the 1956 Francis Golffing translation.

Tuesday, November 24, 2015

all allegories come to an end somewhere - Shaw interprets Wagner - Bakunin, soap opera, and phossy jaw

George Bernard Shaw argues, in The Perfect Wagnerite, that the Ring operas are a response to the revolutions of 1848 and are an allegorical argument for democratic socialism. Maybe so! In Das Rheingold, a greedy dwarf acquires a gold ring of great, ill-defined power. He uses it to force the other dwarfs into an industrial mining operation.

This gloomy place need not be a mine: it might just as well be a match-factory, with yellow phosphorus, phossy jaw, a large dividend, and plenty of clergymen shareholders. Or it might be a whitelead factory, or a chemical works, or a pottery, or a railway shunting yard, or a tailoring shop, or a little gin-sodden laundry [Zola reference!], or a bakehouse, [etc.] (18)

The factory is in the music as well as the text, as eighteen behind-the-scenes anvils bang out the dwarf motif when Wotan and Loge descend into the mine. If Shaw is right about this scene, and it seems undeniable to me, he could be right about others.

In Die Walküre, Wotan begins to play the long game, manipulating events to further the birth of an ideal hero, Siegfried, who can recover the ring from the dragon who guards it. He succeeds, in that Siegfried is some kind of anarchist creature of nature who is beyond wealth and other earthly things, so far beyond them that it is not clear whether Wotan has created a hero or a new kind of monster. He is

in short, a totally unmoral person, a born anarchist, the ideal of Bakoonin [!], an anticipation of the “overman” of Nietzsche. (48)

In other words, a Russian revolutionary, even Chernyshevskian, hero, supreme in righteousness and upper body strength. I love Shaw’s description of Bakoonin forging his magic sword: “Meanwhile Siegfried forges and tempers and hammers and rivets, uproariously singing the while as nonsensically as the Rhine-daughters themselves” (54). You know, like “Heiaho! haha! / haheiaha!” First, Shaw’s summaries are a lot of fun; second, good allegorists know how far to push things.

But then comes the point where Shaw does not push enough. Siegfried slays the dragon, acquires the ability to speak with birds, casually murders his foster father, etc., etc., terrific fairy tale stuff, before encountering and defying his grandfather Wotan – “But all this is lost of Siegfried Bakoonin” (60), and he breaks Wotan’s staff, allegorical representation of the rule of law, and plunges past the illusionary flames of received truth (of, for example, Christianity) into the true Truth, overthrowing Church and State and ushering in the Revolution.

If Shaw is laying it on a little thick, it is because he has still has one scene left in Siegfried and one entire opera left, and he has run out of allegory.

And now, O Nibelungen Spectator, pluck up; for all allegories come to an end somewhere; and the hour of your release from these explanations is at hand. The rest of what you are going to see is opera, and nothing but opera. (61)

By which Shaw means both opera – the usual choruses and ensemble singing and so on missing from the early Ring plays – and what we would call soap opera, because the rest of the story of the ring is about love, sex, jealousy, betrayal, and other melodrama about which Shaw does not care, so he simply expels it from his interpretation.

Indeed, the ultimate catastrophe of the Saga cannot by any perversion of ingenuity be adapted to the perfectly clear allegorical design of The Rhine Gold, The Valkyries, and Siegfried. (63)

It is exactly here that Shaw betrays himself, because even as limited an ingenuity as mine can see that the allegory continues, that Bakoonin is corrupted not by money, to which he is genuinely immune, but by women, and that as a result he is murdered by a rival political faction, Leninists, I suppose. Then comes, inevitably, the apocalypse. Shaw has no better idea than I do what new horrors will fill the vacuum. The soap opera is just as allegorical as the less soapy opera, if I want it to be. As Shaw says, thinking of Wagner, not himself, “Constancy has never been a great man’s virtue” (98).

Monday, November 23, 2015

Shaw creates The Perfect Wagnerite - animated beer casks, the craze for golden hair, and the curse of the foreign music teachers

Reading Wagner gives me the opportunity to read around Wagner. For example, George Bernard Shaw’s little 1898 book The Perfect Wagnerite, in which Shaw soothes the anxieties of Londoners worried that the current vogue for Wagner will go over their heads.

I offer it to those enthusiastic admirers of Wagner who are unable to follow his ideas, and do not in the least understand the dilemma of Wotan, though they are filled with indignation at the irreverence of the Philistines who frankly avow that they find the remarks of the god too often tedious and nonsensical. (ix)

If that sounds insulting, yes, The Perfect Wagnerite is full of insults. On page 135 Shaw insults the Eiffel tower and Handel festivals.

If our enthusiasm for Handel can support Handel Festivals, laughably dull, stupid and anti-Handelian as these choral monstrosities are, as well as annual provincial festivals on the same model, there is no likelihood of a Wagner Festival failing. (135)

An English Wagner Festival would be no worse than Bayreuth, where

[s]ome of the singers are mere animated beer casks, too lazy and conceited to practise the self-control and physical training that is expected as a matter of course form an acrobat, a jockey or a pugilist. The women’s dresses are prudish and absurd… The ideal of womanly beauty aimed at reminds Englishmen of the barmaids of the seventies, when the craze for golden hair was at its worst. (136)

Etc., etc. Has anyone, by the way, come across a novel, of the time of historical, which mentions the 1870s craze for golden hair? It was news to me. More to the point, does this kind of rhetoric convince anyone, ever? No wonder Shaw did not get his English Wagner Festival.

This sort of thing is a lot of fun, and Shaw is a music critic of such depth that he can get away with it.

Abominably as the Germans sing, it is astonishing how they thrive physically on his leading parts. His secret is the Handelian secret. (138)

Meaning that Wagner writes as if the singers and what they are singing is meant to be heard and understood, as if he is a dramatic artist as well as a composer, rather than performed like an athletic feat. “A presentable performance of The Ring is a big undertaking only in the sense in which the construction of a railway is a big undertaking…” (139)

To understand Shaw’s criticisms of Wagnerian singers I have to set aside the great changes in opera singing, performance and recording in the last century. I have to ignore the interpretive subtlety of Dietrich Fisher-Dieskau as Wotan. After all, I know that Shaw is right, that singers as unprepossessing as Elmer Fudd and Bugs Bunny can credibly sing Wagner:

The truth is, there is nothing wrong with England except the wealth which attracts teachers of singing to her shores in sufficient numbers to extinguish the voices of all natives who have any talent as singers. Our salvation must come from the class that is too poor to have lessons. (140)

Now that is a Shavian ending. If I were describing The Perfect Wagnerite in the proper order, the ending would circle back to Shaw’s interpretation of Wagner, the first seventy percent of the book. I skipped it in order to enjoy the insults more freely, and to save it for its own post.

Sunday, November 22, 2015

To my loathing I find only ever myself - notes on Richard Wagner's Ring as literature

I am going to write one post about Richard Wagner’s four Ring of the Nibelunga operas, or really the texts. To do that I need a translation, a book. The book is Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung (1993), edited by Stewart Spencer and Barry Millington, which has German and English texts (translated by Spencer) side by side, along with a number of helpful essays about the operas’ sources, composition, performance, and also the minor side issue of the music. What a helpful book. The translator’s general method is to sound like he is translating the Poetic Edda, with punchy lines and lots of alliteration, while Wagner’s method was to sound like he was imitating the Poetic Edda.

Das Rheingold (1869), Die Walküre (1870), Siegfried and Götterdämmerung (both 1876). I have identified the dates of first performance, but the texts go back to the 1848, with some version of them published – without any music – as early as 1853. Wagner began with the idea of an operatic version of the great medieval German epic Die Nibelungenlied, but kept discovering that he needed to move backwards.

The history of the text and score, evolving over almost thirty years, gives Wagner experts a lot to do. My favorite part of this story is that Wagner insisted that his texts embodied the ideas of Ludwig Feuerbach, until he discovered the work of Arthur Schopenhauer, after which, having changed almost nothing, he claimed that the Ring exemplified the ideas of Schopenhauer. I assume Wagner was as right as wrong each time.

The Ring is a cosmological story, beginning, obliquely, with the creation and ending with the apocalypse. Less symbolically, a dwarf steals a gold treasure from some mermaids, and the pursuit of this treasure by various parties, especially the Norse gods, Wotan and so on, leads eventually to the destruction of the heroes and gods by fire. The dwarf puts a curse on the gold when, in Das Rheingold, it is seized from him by the might-makes-right gods, and supposedly this curse generates much of the subsequent action:

No joyful man

shall ever have joy of it;

on no happy man

shall its bright gleam smile;

may he who owns it,

and he who does not

be ravaged by greed! (Das Rheingold, Sc. 3, p. 98)

But one of the finest subtleties of Wagner’s conception is that there is no curse. No curse is needed to evoke ordinary human nature at its worst. Almost all of the characters – the dragon, the dwarfs, the gods – are credibly human.

The Ring is gigantic enough – Götterdämmerung in particular always seems like it will never end – to include many stories. The Ring is about many things. What struck me most strongly this time was what I will call the Tragedy of Wotan, the Shakespeare-like story of the king with too strong of a sense of fate, the existentialist Odin. He schemes, he acts, he even triumphs, but always with the knowledge that in the end, even for an all-powerful, all-knowing being, none of it matters:

How can I make that other man

who’s no longer me

and who, of himself, achieves

what I alone desire? –

O godly distress!

O hideous shame!

To my loathing I find

only ever myself

in all that I encompass! (Die Walküre , Act II, Sc. 2, p. 152)

What will strike me next time I read the Ring is anybody’s guess. Would a reading of the Ring plays have any meaning to someone who had no interest at all in the operas, the music? I don’t know. Probably not.

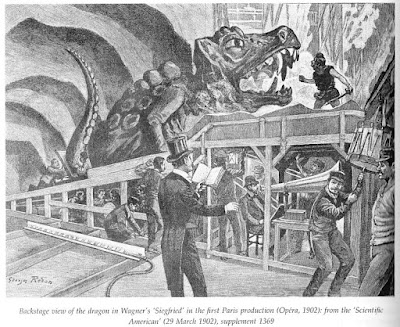

I found that backstage image of Siegfried slaying Fafner the dragon, as portrayed in Paris in 1902, in The New Grove Book of Operas, 2000 edition, p. 586.

Thursday, November 19, 2015

a trap for what the professor correctly assumes is the enfeebled German brain - Gottfried Benn goes angling for monsters

Michael Hofmann’s Gottfried Benn is a bit like a character in a novel about an old man ruminating over his past mistakes. This novel is innovatively presented as a translation of the old man’s poetry and prose, but also including the original German poems, which are sometimes great masterpieces. That last part is the one no novelist can do. Not many.

Benn moves from his early stark shockers (“two hundred pages, thin stuff, one would be ashamed if one were still alive,” as Benn described his own poems in 1921) to a bold lyricism to a loose, conversational style, like I’m meeting him in a bar:

from Nocturne

From the saloon bar the rattle of dice on a wooden tabletop,

beside you a couple at the anthropophagous stage,

a chestnut bough on the piano adds a natural touch,

all in all, my kind of place. (p. 123)

Somehow the booze leads Benn to think of its effect on his primitive brain – he is a doctor, remember – and then to the primitive ocean, long before man,

before consciousness and conception,

no one went angling for monsters,

no one suffered deeper than ten feet,

which if you think about it isn’t so very much.

Benn made one big mistake. In 1933, he “drifted into the Nazi orbit” (Hofmann, p. xvii) and supported them in the minor but real ways a poet can support a bunch of culture-obsessed ideologues. What is impressive about Benn is that within a year and a half he had realized his mistake. “It dawned on Benn that the Nazis were not a bunch of pessimistic aesthetes like himself, but rather imbued with a sanguinary optimism…” (xvii). How many artists disentangle themselves from their bad politics so quickly?

Who knows what might have happened to Benn, but, as strange as it sounds, he was saved by the war. For Benn, a doctor specializing in venereal diseases, military service was like a writer’s retreat. Stationed in some boring behind-the-lines backwater military hospital, he could finally get to work on his writing. Both the first and second world wars were highly productive times for him. So odd.

During World War II, his writing would have got him shot if the wrong people had known he was doing it.

The second-longest prose piece in the book is an extraordinary piece of memoir, “Block II, Room 66” (1944), “the address of the quarters where I was billeted for a number of months” (308). Recruits pass through, each batch both younger and older than the last, the training period shorter every time, “[e]ver new waves of men, waves of blood, destined to dribble away into the Eastern steppes after a few shots and gestures toward so-called enemies” (310). The nation’s leaders become more obvious confidence men and thugs, “club wielding clowns, heroes with brass knuckles” (312); the propaganda grows more rancid and desperate. The “individualist felt like a one-man cosmic catastrophe” (315), the irony being that this is how Benn always felt.

As with Karl Kraus, the rise of the Nazis had the effect of ruining the satirists’ ironies. “Block II, Room 66” has a streak of Kraus running through it. Benn is enraged by the use of German poets in Nazi propaganda. “Listen: in the Naval Review of November 1943… that makes its way through our blocks, a professor for church and international law at a Bavarian university treats questions of war at sea (a church lawyer?) under four aspects,” supporting his claims with quotations from Rilke and Hölderlin:

Now, it’s possible to come at the Duino Elegies from many angles, but to interpret them as in some sense warlike is something they really won’t bear. The allusion to Rilke is a trap for what the professor correctly assumes is the enfeebled German brain. (318)

Then it’s Christmas. Then the Russians come. “The part that lives is not the same part that thinks, that’s a fundamental fact of our existence, and we had better get used to it.” But Benn does get a lot of writing done.

Wednesday, November 18, 2015

Michael Hofmann's translation of Gottfried Benn - unlike Brecht, he’s not even unpopular

It was The Blue Lantern, I believe, who alerted me to the 2013 publication of Michael Hofmann’s translations of Gottfried Benn, Impromptus: Selected Poems and Some Prose. Nearly half prose, in effect. Benn is a strange case.

And yet we’re talking of someone of the eminence of, say, Wallace Stevens, someone most Germans (and most German poets too) would concede as the greatest German poet since Rilke. (xiv)

The horrible thing about that sentence is that it might even be true. “Most Americans would concede that Wallace Stevens is someone they have never heard of” – also true.

The word “concede” and the dig at the German poets gives hints of the difficulty.

Benn’s first book, the 1912 Morgue and Other Poems, is a pamphlet of five autopsy poems, some of which are as grisly as that sounds. A punk gesture.

Little Aster

A drowned drayman was hoisted onto the slab.

Someone had jammed a lavender aster

between his teeth.

[skipping the dissection]

Drink your fill in your vase!

Rest easy,

little aster! (9)

That aster recurs frequently over the next forty years. Some people find it useful to call this Expressionism, but Benn, a young doctor, was just writing what he knew. And what he knew was dissection, skin problems, and venereal diseases. These subjects suited his dark temperament.

A normal life and a normal death –

I don’t know what they’re good for. Even a normal life

ends in an unhealthy death. Altogether death

doesn’t have a lot to do with health and sickness,

it merely uses them for its own purposes. (from “Restaurant,” a much later poem, 127)

I have picked a couple of examples that sound especially prosy in English, but Benn – a slightly older, less shocking Benn – worked with form and rhyme and the usual business. He reminds me of Verlaine sometimes, creating musical beauty whatever the subject.

Ich kann mir keine Bücher kaufen,

ich sitze in den Librairien:

Notizen – dann nach Aufschnitt laufen: –

das sind die Tage von Turin.

I can’t afford to buy books;

I sit around in public libraries,

Scribble notes, then go for cold cuts,

These are the days of Turin.

The tragic speaker here, by the way, is an ill Friedrich Nietzsche; soon, in the next stanza, he will hug the horse. The more conventionally formed Benn poems are from the 1920s and 1930s, but Hofmann warns me that any sense of movement is an illusion of the translator based on his failure with most of the poems from this period.

I’m afraid they were too difficult and idiosyncratic for me to carry them into English in any important way. (xxii)

He gives an example, just two lines:

Banane, yes, Banane

vie méditerranée?

Banana, yes, banana

Mediterranean life?

Says Hofmann: “I don’t think so.”

But Hofmann gives me better than Benn has gotten before:

Thus unsuccessfully transmitted, Benn has no English admirers; unlike Brecht, he’s not even unpopular. (xiv)

And more importantly, he has given me more Benn. Because what this book really gives is not deathless verse, not on the English side of the page at least, but a strong personality, like in a novel. I ought to write one more post about that, the flavor of Benn.

Tuesday, November 17, 2015

Verga's landscape, hellish, poignant - a mist, a sadness, a black veil

I included a grotesque description of a character from Mastro-Don Gesualdo, which is from a section full of grotesquerie, almost nothing but grotesques, the chapters where cholera comes to the land and Sicily, pretty bad all along, turns into Hell.

More Italian literature is directly descended from Dante than I had realized a year ago.

As they went along, he told stories that would make your hair stand on end. At Marineo they had murdered a traveler who kept hanging around the watering trough, during the hot hours of the day. He was ragged, barefoot, white with dust, his face burning, his eyes sullen, trying to do his thing in spite of the Christians who were guarding from a distance, in suspicion. At Callari they had found a body behind a fence, swollen as a wineskin; they had found it from the stench. At night, everywhere, you could see fireworks, rockets raining down, just like on Saint Lawrence night, God save us! (226)

The characters flee to the countryside, to their farms. Amidst this horror, Verga decides to start up a love story, with Gesualdo’s daughter falling for her cousin, repeating her mother’s history, although she does not know it. Love in the time of cholera. Hey, wait, I’ve read that book.

The beginnings of love are inspired by the land, her father’s property, which are foreboding, perhaps from the aura of her father:

The level fields were deserted, shaded in dark. There was a low wall covered with sad ivy, a small abandoned water basin in which some aquatic plants were rotting, and on the other side of the road some squares of dusty vegetables, cut across by abandoned roads that ended up drowning into the thick boxwood bristling with yellow, dead branches. (235)

That does not sound so inspiring, yet the sad landscape contain traces of her lover:

… burned pieces of paper, damp, still moving about as if they were living things – burned matches, torn ivy leaves, shoots broken up into small pieces by his feverish hands, during the long hours of his waiting, in the automatic activity of his fantasizing.

The scene of Isabella’s love becomes, years later, a place of epiphany for her dying father, Don Gesualdo:

But down there, before his property, he indeed realized that it was all over, that all hope was lost for him, when he saw that now he didn’t care at all. The vines were already leafing, the wheat was tall, the olive trees in bloom, the sumacs green, and over everything there spread a mist, a sadness, a black veil… The world was still going its own way, while for him there was no hope any more, gnawed inside by a worm just like a rotten apple that must fall from the tree – without the strength to take a step on his own land, without feeling like swallowing an egg. Then, desperate that he had to die, he began to hit ducks and turkeys with his stick, to break out the buds and the wheat stocks. He’d have liked to destroy in a single blow all the wealth he had put together little by little. He wanted his property to go with him, desperate as he was. (311, ellipses mine)