My final German Literature Month book (look at all of the participants!) will be The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music (1872) by Friedrich Nietzsche, his first book, an imaginative consideration of the psychological impulses that led to the creation, degeneration, and recovery – in the works of Richard Wagner – of Greek tragedy. It is a strange book, not scholarly yet based on the latest German classical archaeology and anthropology, leaping far beyond the actual evidence, difficult, exhilarating, and preposterous.

Greek tragedy is, for Nietzsche, in the first form visible to us, the plays of Aeschylus, a balance between the rational and the irrational, the steady Apollonian and frenzied Dionysian sides of the human personality. The chorus, the music, is the Dionysian side.

It is vain to try to deduce the tragic spirit from the commonly accepted categories of art: illusion and beauty. Music alone allows us to understand the delight felt at the annihilation of the individual. (Ch. 16, p. 101)

A strongly Schopenhauer-like claim, and one with which I roughly agree. Literature, even at its craziest, is typically way over on the Apollonian side compared to dance and music. Poetry moves towards the Dionysian to the extent that it resembles music. I am beginning to sound like Walter Pater, or Pater sounds like Nietzsche.

Tragedy goes into sharp decline in the hands of the innovative parodistic screwball Euripides, mostly because he pulls too much music out of the chorus, destroying the Dionysian side of tragedy. But Nietzsche forgives Euripides, for he is just a pawn of the true villain:

For in a certain sense Euripides was but a mask, while the divinity which spoke through him was neither Dionysos nor Apollo but a brand-new daemon called Socrates. Thenceforward the real antagonism was to be between the Dionysiac spirit and the Socratic, and tragedy was to perish in the conflict... The marvelous temple lies in ruins; of what avail is the destroyer’s lament that it was the most beautiful of all temples? And though, by way of punishment, Euripides has been turned into a dragon by all later critics, who can really regard this as adequate compensation? (Ch. 12, 77)

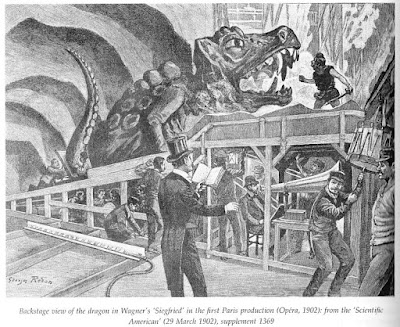

Turned into a dragon! Like the greedy, murderous giant Fafner in Das Rheingold and Siegfried.

The creation of opera by, let’s say, Monteverdi in the 17th century should restore the balance, but Nietzsche does not believe such a thing happened before Wagner. To use Shaw’s phrase, Rossini and Verdi are “opera, and nothing but opera,” not tragedy. I did not understand Nietzsche’s argument, and would be pleased to dismiss it as prejudice, but I am too ignorant to do so.

Our art is a clear example of this universal misery: in vain do we imitate all the great creative periods and masters; in vain do we surround modern man with all of world literature and expect him to name its periods and styles as Adam did the beasts. He remains eternally hungry, the critic without strength or joy, the Alexandrian man who is at bottom a librarian and scholiast, blinding himself miserably over dusty books and typographical errors. (Ch. 18, 112)

Non-Wagnerian opera “is the product of the man of theory, the critical layman, not the artist. (Ch. 19, 115), not even Socratic but, per the previous passage, Alexandrian, desiccated, the province of scholiasts. I know, this is as bizarre and wrong-headed a description of Rossini as I can imagine.

Luckily Bach and Beethoven, alongside Kant and Schopenhauer, created the superstructure – “succeeded in destroying the complacent acquiescence of intellectual Socratism” – that allowed Wagner to save the day, at least for a while.

The end of The Birth of Tragedy is extraordinary. Nietzsche is arguing for the value of the Dionysian impulse, arguing that you Swiss and Prussian and Victorian squares seek out the Dionysian a little more.

The reader may intuit these effects if he has ever, though only in a dream, been carried back to the ancient Hellenic way of life. (146)

What a line – “if”! In a dream, perhaps, but also, possibly, in some other way, such as time travel, or, and this is an example from German literature, madness, like that of poor Friedrich Hölderlin who at times seemed to believe he lived in Classical Greece. I wonder if the line is actually referring to Hölderlin. I wonder if poor Nietzsche ever thought it might refer to himself.

After a pause for the holiday, I will return to the idea of the Dionysian with the help of Walter Pater.

Page references are to the 1956 Francis Golffing translation.