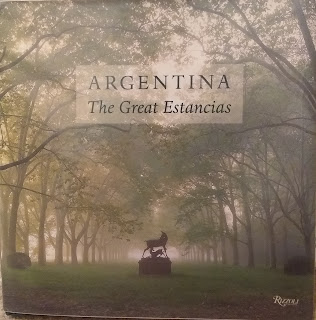

Why have I been reading the 1995 Rizzoli coffee table book Argentina: The Great Estancias? “Estancias” are estates, enormous cattle and sheep ranches, many of which have central houses – mansions – palaces – of great architectural and historic interest, given any interest in Argentinean ranches.

Edited by Juan Pablo Queiroz and Tomás de Elia, photos by the

latter, text by César Aira. There we

go! Aira was at this point a know writer

in Argentina, unknown elsewhere, author of a mere twenty books. This book is a professional gig, and I now

think also a favor for friends. This bit

that I am writing is perhaps of narrow interest, to Airaists and fans of, I

guess, Argentinean ranch architecture, but it is also a tribute to the

pleasures of completism.

Aira is a conceptual artist and a surrealist. His best quality, as far as I am concerned,

is his inventiveness, his screwy surprises.

In The Great Estancias he is on his best behavior, which is

unfortunate, but once in a while there is a reward:

There were also the legendary but altogether real nocturnal attacks by large packs of wild dogs. (185)

Or:

In one of the old buildings, known as la casa de los huesos (the house of bones) Natalie Goodall maintains a collection of skeletons of dolphins, porpoises, and seals. (200)

Those sound like Aira sentences.

Aira is also suspiciously attentive to visiting writers and

to libraries:

That’s at the San Miguel estancia in the Córdoba province.

Even with the ladder, those

highest shelves, how?

This book was quite helpful in filling in the background of

Aira’s subset of historical pampas novels, Ema the Captive (1981), The

Hare (1991), and An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter

(2000). The protagonist of the latter,

the German painter Johann Moritz Rugendas, is discussed on p. 50 – not that

this is five years before the novel is written – and the book includes a

Rugendas drawing that will be specifically parodied in Aira’s novel.

So I learned a lot about Argentinean ranch houses, which are

frankly pretty interesting, and I learned some things about Aira and his art,

which is why I sought out the book.

Aira recommends a book himself:

Lucas Bridges recounted the story of his father, Harberton [the estancia], and Viamonte in The Uttermost Part of the Earth, a beautiful book published in 1948 and reprinted many times. (198)

This is Harberton, with the whale tooth arch, on Tierra del

Fuego. I of course immediately requested

the book from the library.

The joys of completism.

I recommend the book to all amateur Airaists. I was inspired to finally pin down Argentina:

The Great Estancias because of the recent Mookse podcast on Aira. I have not heard the show but I will eagerly

read the transcript as soon as it is available.

For some reason Mookse omits this book, and one other, from a list of

Aira books available in English.