“The Bridge-Builders” leads off The Day’s Work. Kipling is building a gigantic bridge across the Ganges this time, rather than a ship’s engine or polo victory.

In the little deep water left by the drought, an overhead-crane travelled to and fro along its spile-pier, jerking sections of iron into place, snorting and backing and grunting as an elephant grunts in the timber-yard. Riveters by the hundred swarmed about the lattice side-work and the iron roof of the railway-line, hung from invisible staging under the bellies of the girders, clustered round the throats of the piers, and rode on the overhang of the footpath-stanchions; their fire-pots and the spurts of flame that answered each hammer-stroke showing no more than pale yellow in the sun’s glare.

If I am not so sure that I want to read fiction about bridge-building, I am sure that if I do read it I want it to be written by a writer like Kipling, one who does not just know but sees, or perhaps I mean does not just see but knows. What a memory he must have had.

As well as the early part of “The Bridge-Builders” introduces the main theme of the book, it is a bit of a diversion. The bridge is nearly done when the Ganges floods. Is the story about the heroic efforts of the chief engineer Findlayson and his Indian “all-around man” Peroo to save the bridge? No, not at all. Through circumstances too convoluted to describe, the two characters spend the flood trapped on an island, jointly hallucinating a debate of the Indian gods – Ganesh, Hanuman, the Ganges personified (well, crocodilified) – about whether or not the bridge will stand. Ganesh takes the long view:

“It is but the shifting of a little dirt. Let the dirt dig in the dirt if it pleases the dirt,” answered the Elephant.

A strange thing to read in a book about work and duty.

Kipling rarely resorts to actual gods but more typically allows his human-scale characters glimpses of the cosmic:

…an accident of the sunset ordered it that when he had taken off his helmet to get the evening breeze, the low light should fall across his forehead, and he could not see what was before him; while one waiting at the tent door beheld with new eyes a young man, beautiful as Paris, a god in a halo of golden dust, walking slowly at the head of his flocks, while at his knees ran small naked Cupids. (“William the Conqueror”)

The characters fall in love when they reveal themselves, for an instant, as divine. The Day’s Work ends with an uncanny repetition of the idea in “The Brushwood Boy,” where the recurring dreamscape of an English officer in India turns out to be a mystical link to a girl he knew in his childhood.

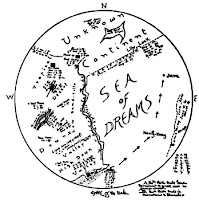

He and she explored the dark-purple downs as far inland from the brushwood-pile as they dared, but that was always a dangerous matter. The interior was filled with “Them,” and “They” went about singing in the hollows, and Georgie and she felt safer on or near the seaboard. So thoroughly had he come to know the place of his dreams that even waking he accepted it as a real country, and made a rough sketch of it.

And Kipling makes a sketch, too. Maybe I should have quoted a weirder bit, like when Georgie drowns and a duck laughs. “The Brushwood Boy” is like a Lovecraftian weird tale of the Dream Cycle variety that ends not with the revelation of forbidden knowledge but rather the discovery of, to use the contemporary word, a soulmate and, as the romance readers call it, a HEA. Weird, weird, weird.

kipling's mysticism shows up even in these "mechanical" stories; let the dirt dig the dirt; let thought do what thought does... he must have become quite familiar with hinduism and associated religions while a young journalist in india, as well as reporting on major construction projects.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much for writing these posts, being a Kiplinger is a lonely path, finding insightful readers of Kipling is a rare occasion.

ReplyDeletehttps://greatwarfiction.wordpress.com/ has some imteresting pieces on Kipling.

Delete"Georgie drowns and a duck laughs"??? :-s

ReplyDeleteMudpuddle - yes, I think that is right. The best place I Know to see it is in Kim, that great celebration of Indian multicultrualism.

ReplyDeleteCleanthess - Kipling is so full of treasures. And puzzles. I am sure I will read all of his short fiction, at least. I would love to have a little set of it, if anyone would print up such a thing for me, which seems unlikely now. Even a period piece like "A Walking Delegate" had the most amazing descriptive passages about the horses, especially their movement. What an eye.

Roger - thanks for the pointer. Really interesting, and all new to me.

Di - you know, one of those dreams where you drown, and the main problem with drowning is not that you die that a duck laughs at you, and when you wake up you are still irritated at that duck.

Talking about Kipling's puzzles. Anthony Burgess (or was it Paul Theroux?), during one of his conversations with Borges, was offered the chance to try to crack together the mystery of Mrs. Bathurst and see if it was a good story, he refused, to this refusal Borges only replied, "it must be a bad story then".

ReplyDeleteWhat a missed opportunity, but only to be expected, since Theroux had considered ridiculous Kipling's tale 'At the End of the Passage', where a man photographs the bogeyman on a dead man's retina and then burns the pictures because they are so frightening (which, by the way, is pretty much the plot of the Sinister movie franchise).

A supernatural entity being captured on film and being able to see us from inside the film, and harm us, is the key to unpacking Mrs. Bathurst, IMHO (and, by the way again, it's a plot device used a lot on movies like The Curse and The Ring and...).

Now I am almost frightened to read "Mrs. Bathurst."

ReplyDelete